Power of Movement: Insectivorous Plants

Darwin observed that many elements in nature act on plants as natural selective forces: light and water availability are two of the most important. Darwin’s experiments showed how plant movements allow species to adapt to many natural selective forces. His work also led to the discovery of plant growth hormones in the twentieth century. |

||

|

|

||

| Darwin studied many plants that grow in nutrient-poor substrates, like bogs – the Venus-fly-trap, pitcher plants, bladderworts, and sundews, to name a few. They have evolved specialized leaves with the power of movement that capture insects and secrete enzymes to digest animal protein. | ||

|

|

||

|

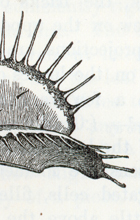

The “fly-trap” closes almost instantaneously to movement on its 3-6 trigger hairs in the inner broad sides of each leaf-trap. | |

|

Illustration from Insectivorous Plants by Charles Darwin (1875, p. 287). |

||

|

“The whole leaf of a Dionaea could not jerk forwards unless a very large number of cells on one side were simultaneously affected.” Charles Darwin, Power of Movement in Plants , p. 547. | |

|

Ink drawing of Venus-fly-trap (Dionaea) by Carol Lerner, 1982. |

||

|

Watercolor of purple pitcher plant (Sarracenia) by Carol Lerner, 1982 |

|

|

|

||

| Sundew tentacles, stimulated by a bit of raw meat, “begin bending in 10 seconds, to be strongly incurved in 5 minutes, and to reach the centre of the leaf in half an hour.” Charles Darwin, Insectivorous Plants, p. 262. | ||

|

|

|

| Print of a watercolor of Roundleaf Sundew (Drosera) by Claus Caspari in Mitteleuropäische Pflanzenwelt by R. Kräusel, 1956-60. | Drosera rotundifolia from Darwin’s Insectivorous Plants. (1875, p.10) | Drosera rotundifolia from Darwin’s Insectivorous Plants. (1875, p.11) |

|

|

||

| Next: Natural and Artificial Selection | ||